The Politics of Disability

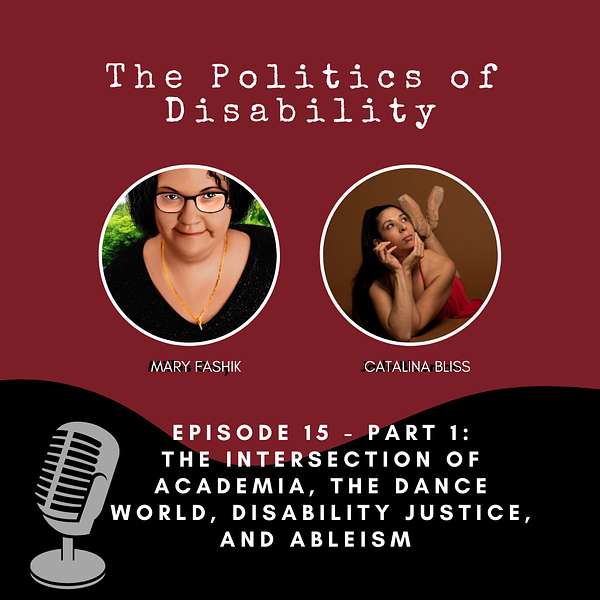

Hosted by the founder of the Disability Justice movement Upgrade Accessibility , Disability Mentoring Hall of Fame inductee, and two-time award winning podcaster Mary Fashik.

Portrait sketch: @jenny_graphicx on Instagram

The Politics of Disability

The Intersection of Academia, The Dance World, Disability Justice, and Ableism - Part 1

Content warning: Explicit language and mentions of ableism

In the first part of the season one finale, Mary and Catalina discuss ableism in academia, the dance world and Disability Justice.

Born in Medellin, Colombia and raised in Fairfield County, Connecticut, Catalina earned a BA in Psychology at Western Connecticut State University in 2011 and completed all coursework for MS degrees in Psychology and Criminal Justice at Central Connecticut State University in 2015. In 2020 and 2021, she received RISE scholarships to attend American Ballet Theatre’s National Training Curriculum’s Teacher Training Intensive for levels Pre-Primary through Level 5. ABT provided these scholarships to Catalina for her work as a social justice advocate and commitment to working with marginalized dancers, particularly with disabled dancers. Catalina is now an ABT® Certified Teacher, who successfully completed the ABT® Teacher Training Intensive in Pre-Primary through Level 5 of the ABT® National Training Curriculum (NTC). She has over 15 years of training in ballet and trains under Zimmi Coker (ABT corps de ballet & ABT NTC Pre-Primary-Partnering), Michael Cusumano (former ABT company member), and Rachel Zervakos (ABT NTC Pre-Primary-Level 5). She is also certified in Progressing Ballet Technique and has training in lyrical and jazz, as well as experience with choreographing dances for and competing in regional and national dance competitions with ballet and lyrical solos. Catalina works with all dancers with emphasis on providing an educational experience that is respective of social justice and intersections of oppression. Catalina brings her perspective as a disabled Latina and her vegan ethics of compassion and harm-avoidance to her teaching to ensure that every dancer feels respected, protected, and valued in their entirety.

Catalina enjoys using her platform to advocate for social justice through a disability justice framework and to speak about the many factors that prevent marginalized dancers from accessing equitable dance education and advanced training. Catalina regularly engages with Upgrade Accessibility to address social justice through a disability justice framework.

You can follow Catalina on social media here.

The Politics of Disability was named Best Interview Podcast at the Astoria Film Festival in both October 2022 and again in June 2023.

[music playing as Mary speaks]

Mary: Hello everyone, and welcome. My name is Mary Fashik. I am the founder Upgrade Accessibility and your host. I’d like to thank you for joining me today, at the intersection of disability and politics. The road ahead can be a bumpy one, so buckle up and let's navigate this journey together.

[music playing]

Mary: Hello and thank you for joining me today. Would you please introduce yourself to the audience?

Catalina: Hi. My name is Catalina. I'm a disabled dancer and teacher and I'm Latina and from Connecticut.

Mary: I am, like, super excited that you’re here. Because you know I've been telling you forever. Like “We need to sit down and have a conversation, other than what we do on Instagram live. So I am so excited and everyone should buckle up because it’s going to be a wild ride today. Talk to me–because this is something that I ask every guest, because this is such an important question. We all have defining moments in our disability journey. Talk to me about what was a defining moment in your disability journey.

Catalina: This is a good question. I had to think about this some because when it finally clicked for me that I have disabilities, it dawned on me that I'd had it my entire life and didn't know. So, I grew up with ADHD. When I was a child, I think I was like eight when I was diagnosed. It wasn't called just ADHD then it was you could be ADHD or you could be A.D.D..

And I was diagnosed with ADD. So now that's what we call inattentive subtype ADHD. That's how it's broken down. Now it's the subtypes, and they just call it ADHD with one of the three subtypes. So I was diagnosed with that at eight and it wasn't until I was in probably I think grad school when it finally registered with me that it's like, “Oh, that fits.”

When I started, I was in the criminal justice program at Central Connecticut State University, and I was working on a second master's degree and all the course content for that. And it was right after I was diagnosed with C-PTSD that it finally occurred to me that I was like, “Oh, okay.” And I started looking at what disability really is. And it was that legal definition of, Oh, it's a mental or physical illness that affects major life activities or it substantially limits them. And…huh.

Okay, so both of these conditions I have are that. If I think about my ADHD, it limits my ability to drive a car, to work, to sleep, to, to everything. So yeah, that's definitely major life activities. So once that finally clicked and I realized that I should be getting accommodations and doing these things like, “Oh, okay, I should do that.”

I was probably 22 or 23. So I'd gone from the time I was 8 until the time I was almost 23 before… “I'm disabled. So that's what this is.” And it’s just like, “Why has this never happened before?” And I'd heard about accommodations while going through my undergrad. First day of class. Every single class the teacher reads from the syllabus, “If you have a disability, contact disability services, you can get accommodations.” I'd heard this before. I knew that I was eligible for extended time on tests, but that was never something I needed. In fact, I had always finished first. So, I just never made that connection of a disability and should be asking for X, Y and Z. Never crossed my mind and nobody said, “Oh, you fit here, you can go do that.”

So that made a big difference and it started opening other doors for me and closing doors at the same time. It wasn't the disability so much. It was people. [laughs] It was the people, everybody else, society that closed doors.

Mary: But it's ironic that you mentioned when you were in college, and the syllabus, and you had to contact disability services. Because, like, throughout high school, they called it ‘special ed.’ And even though I was mainstream among my non-disabled peers, and I was in honors classes, when it came to standardized testing, I would always be put in with the disabled kids. And I used to take offense to that. Like, “I don’t understand why I have to be in this room with disabled kids, when I’m in honors classes.” No one bothered to explain to me what “accommodations” meant. How would I know at 15 or 16?

Now, I’ve said this before, the Americans with Disabilities Act passed shortly before my 13th birthday. So, I was like, “Oh okay, this is for me.” Like, then they started to pay more attention to the disabled kids. But even though 504 was in place, the ADA made administrators more aware. And we never called it an IEP when I was in school. I don’t think so. Maybe we did. I just know that the woman who raised me had to meet with the Director of Special Education every school year to talk about what I needed. And they would say, “Well she's in honors classes. She doesn’t really need any accommodations.”

And that wasn’t true. I needed to be able to leave class 5 minutes before the bell rang. Because my high school had 4,000 kids in it. I didn’t need to be in the hallway with 4,000 kids trying to navigate my motorized wheelchair in the hallway. So, I needed to be able to leave early at the end of each class–which meant the teachers had to give out the homework assignment before the end of class. And if I left early, sometimes I didn’t get the homework assignment–things like that. And just, you know, in college, I was like, “Well I don’t need any accommodations.” But I actually did. And I wish I knew then what I know now. Isn’t it weird how we’re never taught these things?

Catalina: Okay. So, when the very, very first time that I asked for accommodations was in grad school, right after I was diagnosed with C-PTSD, and I started to get really sick and I was like, “I need something, like, this is not working out.” So, really, really minimal stuff. I asked for the doors to be closed to the classroom because (I still am) I was really, really sound sensitive.

And for me, hearing very loud sudden noises was a problem. Plus, I should have been doing that all along because stuff that was going on in the hallway was distracting for me. Like I should have been doing that my entire life, so I asked for that. Something simple that takes 2 seconds, you know? And then the other thing I asked for was extended time on assignments, not extended time for tests–extended time for assignments. Because there was a situation that I had therapy I think it was like the morning of or the night after, like a class that was like very, very challenging for me. And the class that I had the next day, I was struggling to get my homework done because I was just like so heavily triggered the day before that it was like, this is not happening.

And disability services was like, “Sure, no problem.” And it was even in the combination that they suggested that people like lessons list on the website. It's like, “this could be a thing that you need.” So I wasn't asking for anything outlandish and none of my teachers had a problem with this. Except one. So this one teacher was for criminology.

His name was Dr. Shamir Rattansi. And I'm never going to forget this because one of my classmates was like, “Yeah, he's really elitist.” And the first day of class before my accommodations would even come in, before anything was said to any of my teachers. He had told the story about a kid who needed accommodations because someone in class said, “Oh, what was the weirdest accommodations somebody asked for?”

And I guess they had asked for like to be tested on like a certain number of chapters at a time instead of it being broken up a different way. Because I guess that's what they could manage, whatever. And like it was like a joke to him. And then he was talking about some kid that had had a panic attack on the elevator like it was funny. And like, “Why is this funny to you?” And I'm like, this should’ve–this was a red flag. Like, I should have known right away this is going to be a problem. And sure enough when my accommodations came through, it was okay for a little while and then… and then it wasn't okay. And he disclosed my disability to my department chair, who was also my employer, because I was working as a grad assistant.

And they pulled me aside while I was at work and they were like, “Oh, you should cut back your classes, you can handle it. And there are people, you know who are really prepared to be in this class who still struggle with it. And you, you're coming from a psychology program and not from criminal justice. So, this is going to be harder for you.”

And I’m like, go fuck yourself, seriously, go find the longest pole and fucking sit on it. Because yeah, I came from psychology, but my background and my research was all on criminal development. So while I was in my undergrad, I took criminology, I took forensics, I took all of the Justice and Law Administration classes at my undergrad. In preparation for this. I was more prepared than everybody else who was supposed to be there.

Even in my psych grad program, all of my research was on juvenile serial sex offenders. I had been doing criminology and criminal development the entire time. It wasn't that I wasn't prepared. It was that I was taking a huge course load and I was disabled and this is what I needed. And this was the only class that I was behind in assignments on.

And you know what? He went to every single one of my teachers and asked about my accommodations, whether I used it or not, which is illegal. It says it right on the top of the accommodation letter: ‘You may not discuss this with anybody other than the student or the head of disability services.’ And he discussed it with everyone except those two people.

And they, I guess their suggestion was that I should drop the class and take it when I had a lower course load. And I said “Fuck you. Fuck you.” The whole purpose of the accommodation is so that I can function in the way that I want to function, independently. If I were not disabled, I would be doing this without problem. And I was all along.

I had always taken a larger course load, always. Everybody else takes three classes. I would take four or five, always, until I got sick. So, this wasn't like I was looking to do something outlandish. I was looking to live my life as I always lived it. And I could if he had just granted my accommodation like he was supposed to do.

I reported it. I reported to the school. When I went to disability services–the head of it–right away, I told her. She said: “This is so illegal, this is completely illegal.” And I tried to follow through with it and I dropped out of the class right away. Like, “I don't want you grading me.” Forget me being able to do it or not.

“I don't want you grading my work. I don't trust you. You're a biased asshat. So we're not doing that.” So, I dropped it and then I asked for a different academic advisor because one day I had been working in the grad office and my current advisor had come up to me and was asking me questions about whether I was struggling to get my work done.

And he was just like looking over everything I was doing and I'm like, “Why aren't you doing that with the other grad assistant? Why are you doing that to me?” And I'm like, “You know what? I don't know if something was said between the two of you, but I don't want to find out. I don't want you helping me make choices about my academic career. I don't trust you.”

So, I asked for somebody else. And who did they give me instead? The department chair who is involved in this whole thing. And I'm like, “Are you serious? I have an open complaint against this person, and against another teacher. And that's who you assign to me? Like this is a shit show. You’ve got to be shitting me.” So now, in retrospect, knowing what I know about disability law, I should have sued the school. [laughs] And you know, things would have been very different.

I ended up going back a few years later because I tried to finish my thesis, which I ultimately couldn't do because of this, because it was just, it just got so drawn out. And it was just like, why am I putting myself through this? But I had gone back to the school to try to do it. And at that point I had Sweeney then.

So, I called the school. And a lot of schools don't realize that service dogs: they're not an educational accommodation. They're just a general access accommodation. And at that point, the school isn't “Oh, it's a school,” it's “This is a building that people can come and go from.” So, getting to have access with a service dog is no different than getting to have access with a wheelchair.

So, I had called the school and I was like, “I'm coming with my service on such and such day.” And they were like, “Oh, us, let's find out if we can do that.” I'm like, “No, no, I'm not asking for permission. This is a courtesy call. I'm telling you that I am coming on to campus with my service dog, period. End of story. I don't need your permission for this.”

So, I learned by then, like this is how we address it and were I to go back to school now, it would be a very, very different story. And in fact, it was when I went and did my teaching certification with American Ballet Theater, which of course they’re not a school in the same sense that a college or graduate school is.

But I met with them and, in fact, they're not even required to give any kind of real accommodations. They're exempt from a lot of stuff. But I contacted them and I said, “This is what I need. This is what I want. What are we doing?” And they were like, “Sure, no problem.” And you know what? They gave me extended time without question for both courses.

They gave me a lot of extended time and they had no issue with it. And it just goes to show that when people let disabled people lead and say, “This is what we need and this is what has to happen,” everything goes fine. Like the world didn't burn because I had extra time to prepare, you know? It was just it was so ridiculous.

It was just the most absurd thing in the world. And now any time I get the chance to say this happened at this school, and this person did this to me, I say it. Because I want people to know that this is what the way things are and this is what this place is like and this is what you can do instead.

Don't fall for this shit. You're entitled to things. Don't let anyone tell you that you're not.

Mary: Like for me, in high school, when I took my SATs, I took them with everyone else. And I didn’t do really well, because I don’t do well with timed tests–not because of the time itself, but because of having to fill in the bubbles. So, physically, for me, having to fill in the bubbles (and they have to be filled in perfectly), with my disability, I have coordination issues, fine motor skill issues. So having to do that is very time consuming.

So it wasn’t that I was having problems with the cognitive stuff. It was literally just filling in the bubbles of the ridiculous test. So, my counselor figured out that I could ask for more time. So, they literally gave me all day to take my SATs. And when I had all day to take my SATs, my scores went up much higher. And between that and my GPA, I got a scholarship for college. But imagine if my counselor didn’t say, “Hey, you know what, we can give you more time, so you're able to do what you need to do. Not rush. And fill out the sheet correctly and all of that.

But I look back, and I’m like, “Why did I not have someone with me who could fill in the bubbles for me?” But again, we’re talking about the 90s. If we knew in the 90s what we know now, things would have been so much different. These things have been there since the ADA was signed into law. But we weren’t educated. And also the education system is inherently ableist, has always been inherently ableist, and will always be inherently ableist. That’s just how it is. And since you mentioned taking tests for being able to instruct ballet, and you’ve kind of touched on this, but why is there a lack of accessibility and inclusion in the dance world (specifically ballet), and what can be done to make it more inclusive and more accessible?

Catalina: Okay, this is a big question. All right. First off, what needs to be done to make it more inclusive and accessible is that non-disabled people need to shut the fuck up and get out of the way, and let the disabled dancers lead. That's number one. [laughs] That addresses a lot of issues. And then number two is that people in dance need to stop looking at accessibility and inclusion as something that is not immediately tied to disability.

So, what I see now, and I think you could ask pretty much any disabled dancer and they'll likely connect with this. But what's happening now, and we can thank adult ballet for this, is that when we hear about accessible dance, what they really mean is “This is a space for a whole upper middle class to high wealthy income white adult women.” That's what they really mean.

And there's this massive disconnect, because if you ask any disabled person when they hear the term “accessibility and inclusion” right away, they're like, “Those are our words. You don't talk about accessibility without talking about disability.” That's what it means. You know, you've got a website and you click accessibility, it's not going to the part that makes you feel good because you have a different body shape than somebody else. It's going to the part that makes sure that, you know, if you're deaf, you can hear what's going on here, that if you are blind, that it’s accessible for screen readers, that if you need text in Braille, that you can get that. They go together, you know, they're two peas in a pod. It's one in the same.

And dance doesn't get that. They just co-opted the language and they've made it their own and they've taken disability out of it. So, when I see someone that says,” Oh, this is an accessible class,” I know that they're not talking about me. They're talking about everybody except me.

And I had just discussed this the other day. A friend of mine had brought it up to me that there was a piece in the New York Times about this person, a white woman, teacher, dance teacher, who was offering these accessible classes and nothing to do with disability whatsoever. Not at all. She wasn't disabled. They weren't classes for disabled dancers.

Nothing. It had nothing to do with us. And they were talking about how this person is like being lauded by other big names. And I'm just like, oh, so a white, non-disabled woman is being given a pat on the back by other white non-disabled people for appropriating disability culture. Great. Fantastic.

Mary: I'm going to interject here for one second and say yes, you can appropriate disability culture. That is very, very, very possible and it happens all the time. Sorry. Go ahead

Catalina: No, that's okay. I mean, any time someone is talking about inclusion and the next word out of their mouth is, “oh, we're making this accessible.” That's a disability concept. That's ours. We came up with that. You should be giving credit to disability advocates, activists, whoever, and saying, this is not my invention. This is from here. And that's okay. It’s okay to draw from those concepts, but you need to give us credit and you should be including us. You know, if you're going to make something accessible, then make it accessible, right? If it's not going to be disability accessible then it’s not accessible. That's not what accessibility is. You just mean that you're making it so that the people that you identify with can feel included.

So, you're really just you're not being inclusive, you're being highly exclusive. So, I had seen this going on and I had just brought it up and I'm like: the only people who should be teaching accessible dance and calling it accessible dance are people who understand what that means. Which means it should be run by disabled people, disabled dancers. Disabled dance educators should be leading the way here. We know how to do it. We've been living with this. We understand what it means to be disabled. We understand what accommodations are. We understand how to create accommodations. We understand what we can and cannot do, right, and what we should and should not be doing. Like I will never, ever, ever offer a class in ASL.

Even if I were to learn ASL, I would never, ever do it. It's not for me. It's not mine to take. I would be sending students to deaf dancers to do that. And yes, deaf dancers exist who teach classes in ASL. They're out there. They should be getting paid for that just as much as I should be getting to take up the space of offering adaptive classes with accommodations for mental illness. Like everybody, I feel that when we look to privileged people, they're more than happy to encroach upon everybody else's space, but heaven forbid if someone steps into theirs.

Mary: I always say, “Don't occupy space that doesn't belong to you.” I had someone lump my account in with Black creators. And I said to them, “I really appreciate you recognizing the work I’m doing, but I am not a Black woman. I am a woman of color. I am a Brown woman. I do not want to occupy a space that is not mine to occupy.”

And I think if people, especially non-disabled people, understood that disabled people have a hard enough time occupying space, we don’t need them to take up our space.

Catalina: It never ceases to amaze me that the people with the most privilege are the ones who are always saying that they have the least and they're always looking to creep into areas that aren't theirs. And I guess that's the colonizer mentality at work. Why would you want to be here? This is hard.

It's extra work. Like, when I'm creating classes, I'm making sure that I'm not using music that's going to be offensive to anyone. I’m carefully monitoring how I speak, not just the words that they use, but the pace that I speak at, the tone of voice, my volume, that I'm facing the camera, so anyone who's hard of hearing and reads lips can do that more easily.

I'm speaking as clear as possible, so I'm making sure that I have to use my vanilla voice. Not because I think that that's going to be bias against me, but because I know it's easier for people to understand me, especially if they are hard of hearing and reading lips, when I'm making sure that I'm really enunciating everything and speaking without an accent. And why do they want to be here?

And it occurred to me that it's because they don't get that this is what it really is meant to be, that when they say, “Oh, I'm offering an adaptive class,” in their mind, it's not this. To them, it's, “Oh, I'm doing creative movement with scarves.” That's an adaptive class to them. Maybe that is, that’s adaptive for some people, but not most.

I mean, most of the disabled dancers I work with (or actually every single disabled dancer I work with) takes a regular ballet class. Are there accommodations in place? Absolutely. But they're still doing the same class that everybody else is. And these non-disabled dance educators–they don't get that. They think that we can't do what everybody else does.

So to them, in their mind, “Oh, it's easy to run these classes” because they don't understand the work that has to go into it to make a true dance class, especially a ballet class, actually accessible.

Mary: I just want to say I took one of Catalina’s adaptive accessible classes, and I’m not one for ballet. Zumba is more my pace. But I truly enjoyed Catalina’s class, because of what she just talked about. She made it accessible. And by making it truly accessible, it was enjoyable to me. And I think that’s where we lose the plot is: I did yoga and it was for, like, older people and people who had mobility issues. But I never really enjoyed it because it wasn’t truly accessible for me. It’s so important that non-disabled people understand and I don’t think that they can truly understand because they’re not disabled. Like you said, let disabled people lead because we have life experience.

Catalina: About that class that we did for Camp Access: That's a perfect example because I feel that dance education should be–we should be excelling at this. We're creative. What is accessibility and accommodation if not an area in which we're looking for novel means to reaching an end? Shouldn't this be something that we're the best at? Why do they suck at it? And it's because they just don't try.

And they just have this stagnant, close minded, negative, biased view of what disability is. And to me, any dancer that sprained their ankle and been out on injury should have an idea of what accommodation is. They should get it and they should go look, I just need to adjust X, Y and Z. We should be doing as well.

And instead they just do a poor job and encroach on an area that they don't belong in. And when it's in their mind too hard or they don't get it, they just push people out. Why are you here? Don't be here. You can't do it. Fine, you can't do it. Don't be here. Don't say that this class is just going to be too hard for you or we just need to not do an actual dance class.

Just say that you don't know what you're doing and leave. Let somebody else in–who does know what they're doing.

Mary: I've had people say that to me on occasion. They said, “Well, let's try this one thing.” Like this one adjustment or whatever it is. And then when it doesn’t work, they’re like “Well, I don't think this is for you.” So yeah, I’ve had that happen to me. Let’s tie this into disability justice. What are one or two misconceptions, like the main ones, that non-disabled or even disabled people have about disability justice?

Catalina: First one and this might be like the one for me. And I think you deserve the credit for really bringing this to the forefront and it’s that: disability justice is not disability rights. They are two different things and the differences between them are massive. And again, you get the credit for this, for saying that disability rights is very much rooted in white supremacy.

And I don't know if it was you or somebody else or you've likely said this as well, but that disability rights is a way for very, very privileged disabled people to make sure that they can realize the full benefit of their privilege and that they're not being oppressed in their privileged existence. So it’s a perfect example, is that white disabled people, so long as they can realize the full benefit and privilege of their whiteness, to hell with everyone else. Disability Justice says “who's missing, who's getting nothing? And how do we make sure that they get everything that everybody else gets and that they can actually get it, actually benefit from it, actually utilize it and take part in a way that is meaningful and effectual for them?” So they’re two very, very different things to me. Disability rights centers, those who have the most among us in disability justice centers, those who have the absolute least.

Mary: I did make a statement about disability rights being rooted in white supremacy. The other part of it was Imani Barbarin. I don’t want to take credit for something I did not say. So the second part of what Catalina was referring to was, I believe, said by Imani Barbarin, who is a Black disabled woman–a Black disabled advocate and activist. Will you talk briefly about how disability justice is rooted in social justice which goes back to Black activists? Because we really need to talk about that.

Catalina: Okay. I mean the most obvious and straightforward answer is that disability justice is a form of social justice. It’s essentially addressing the same thing in a more concentrated format. So social justice to me is kind of analogous to how when we talk about civil rights, we talk about disability rights. Disability rights are upon civil rights. So, disability justice is a form of social justice.

And essentially, it's taking the perspective of saying, okay, we're looking at these people who are experiencing multiple avenues of oppression and are also disabled. So, it's not just “you're disabled, it's you're disabled, you're a person of color, you're a woman and you're Jewish.” Take any amalgam of things at one from which one could experience oppression and boom: disability justice for you.

So again, it's looking for those people who everyone else just leaves out and it's looking to say, how do we make sure that you can enjoy the benefits of existence, that you can exist in a way that is really fair and that you can thrive in life how you want to thrive, and that you're not constantly struggling and that you can do whatever it is you want to do with your life without constantly being pushed out by those who have fewer avenues of oppression than you do.

So, I guess the simplest way to tie it back in: when I think about it in terms of dance, I know that one of the founders and original creators behind Disability Justice was a disabled dancer–a Black man. He came up with this form of hip hop that he called Crip Hop. And no one ever talks about that. And I think especially in dance, like, how are we missing this?

Like, this is a big thing, which again, we should be good at this and we should know more about this because this is really part of our history.

Mary: We’re all out of time for this episode. I know, I know. Just when things were getting good, too. That just means you’ll have to come back for part two.

[music playing while Mary speaks] Thank you for joining me for this episode of the Politics of Disability Podcast. As you navigate your journey, remember: disability is political; disability is messy; disability is not palatable--nor does it have to be.

[music playing]